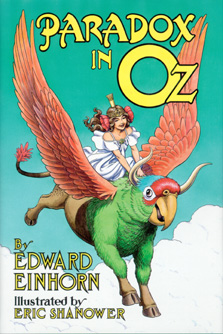

Find out more about Paradox in Oz |

An Interview with the Author of PARADOX IN OZ, Edward Einhorn Conducted in late 1999 as the book was going to press |

|

Q. How did you decide to write PARADOX IN OZ?

EINHORN: I met David Maxine, the publisher, about three years ago, through a mutual friend. We are both involved in theater--I write and direct, and he designs. He even helped with one of my projects, a play I wrote called THE LIVING METHUSELAH. I don't remember whether it was he or Eric Shanower who first suggested that I write a short story for OZ-STORY, but I had certainly talked with both of them about our mutual love of the Oz series. In any event, that led to my writing "Ozma Sees Herself" for OZ-STORY #3. At the publishing party for that magazine, Eric, David and I started talking about the idea of a new Oz novel. I was quite excited about it, because the Oz books were what first brought me to the decision to be an author when I was a child. When Eric said he would be interested in illustrating the book, I knew that I couldn't let the opportunity go to waste. So I wrote up an outline, and I sent it to them. They seemed enthusiastic, so I continued from there.  Edward Einhorn, Eric Shanower, Rachel Cosgrove Payes, and David Maxine Oz-story No. 3 Publication Party (1997) Q. When did you read the original Oz books and what was their influence on you, if any, both in your life and in writing PARADOX IN OZ? EINHORN: As I say in my introduction to PARADOX, I don't know if I would have become a writer if not for the Oz series--and my brother, who deserves credit for introducing them to me. For a while, he had three options for me when we would play together--read Oz, play chess, or play with his castle. Now I've written an Oz book with logical puzzles and a couple of castles. Be careful of what you say to children. When David Maxine first asked me to write the book, I was working on a play in which I had thrown a few allusions to Oz--so I definitely still had Oz on the brain. When I actually wrote the book, I tried to be faithful to the things that had led me to love the series in the first place. I wanted to keep the tone, while still inserting my own mark in the style. I'm simultaneously a traditionalist and someone who loves innovation. Thus, much of the book is much like the old Oz books, yet it also has some twists that, I hope, are very uniquely my own. Q. PARADOX IN OZ deals with time travel paradoxes and alternate worlds. Tell us about your interest in these subjects and how you incorporated them into the story. EINHORN: I've always been both fascinated and frustrated with time travel stories. On the one hand, I love them conceptually. On the other, I almost am never satisfied with the way they resolve the inevitable paradoxes that arise out of any time travel novel. So my first idea was to parody that--write a novel that deliberately doesn't make sense if you put it all together. The character of Tempus seemed perfect for that, because he allowed me to deliberately play with all the paradoxes. Eventually, however, I got stuck in my own trap. The truth is, every book has to have its own internal logic, and even if I was making up my own rules, the rules needed to be consistent. And since it was a book dealing with time travel, the rules were insanely complex. On the one hand, that gave me an opportunity to finally write the time travel story that really works. On the other hand, it meant I had to write a time travel story that really works. I began to understand the problem all those other writers had been having. Eric and David were very helpful to me during the first drafts, because they would point out when I got the internal logic wrong. Mostly, I want all that to be in the background while you read the book, accessible if it's the sort of thing that interests you (as it would me), but not necessary in order to appreciate the book. Q. Why did you choose Ozma as a main character? EINHORN: Ozma had been the protagonist of an earlier story I wrote, and I had developed a strong affinity for her as I was writing. Although she is a major figure in the Oz series, I felt that she was more of an enigma than most of the Oz characters. After LAND OF OZ, she becomes almost too perfect and distant. I wanted to write an Ozma that people could identify with-still the ruler of Oz, but also capable of more human (well, in her case, fairy) emotions. So my Ozma becomes frightened sometimes and even occasionally makes a mistake. Yet she is still able to serve her people by saving them from a major crisis--not that I want to give away the ending. Perhaps she doesn't save them. Perhaps she fails totally, and Oz can never recover from her terrible, terrible errors. I'm not saying. Q. Where did the character of Tempus the Parrot-Ox come from? EINHORN: I needed a way for Ozma to travel through time, and I wanted her to have a companion who was unique to my book. Suddenly, the idea of combining the two occurred to me. I was a little sheepish about the Parrot-Ox pun at first, but now I think it really works, especially in the title. He's both a fantastical creature and a play on words, which underlines the sort of game playing one can expect from him in the book. Q. Explain Dr. Majestico's background before PARADOX IN OZ. EINHORN: Dr. Majestico began as a character I created for an experimental play entitled MY HEAD WAS A SLEDGEHAMMER by Richard Foreman. The play was written with just lines, no characters or stage directions, and I had to create the full scenario for the production. In the play, Dr. Majestico is a mad scientist/magician who creates his assistant during a magic act, only to find that she refuses to act in any way he desires. The character proved to be very popular, and I started incorporating him into a number of things I was working on, at the time. He popped somewhat unexpectedly into Oz when I was writing the outline. As soon as he put him in, I thought that this where he belonged all the time. Right now I'm writing a play entitled "Dr. Majestico's Magic Box" that brings him back to the stage from which he originated. And he appeared again in "Unauthorized Magic," my most recent short story in OZ-STORY #5. It's all the same character, though I think the stage version is from an alternate, even weirder universe. Q. Tell us about the logic puzzles you incorporated into PARADOX. How did you translate them into Oz? How did you choose which puzzles to use? EINHORN: I've always been a fan of logic puzzles, since I was a child. I think my interest may have started when my brother first read the Alice books to me. There is a lot of Alice in the tone of PARADOX IN OZ. Yet logic puzzles can be found in many good children's books, including the original Oz series. I remember enjoying the discussion about the wishing pills Tip ate in LAND OF OZ as being particularly fun when I first read that book. I think, as a child, so many things don't make sense that it's enjoyable to have a book which points out all the nonsense around you. When you're older, of course, you understand everything. Q. The original Oz books often are contradictory in their details, yet you've implied a solution to such contradictions in your story. Can you elaborate on that? EINHORN: One of the things I wanted to do, since I was writing about paradoxes, was to incorporate the existing paradoxes in the Oz series. I was strongly confronted with them first while I was writing "Ozma Sees Herself." I described Ozma as a blonde, forgetting that in later books she was described as a brunette. Then, when re-reading all the Oz books, I was struck by how many times they contradicted each other. So at first I was just going to make that part of the theme, without solving the contradictions. Then my urge to have a book that would both use the paradoxes and solve them grew, and I came up with a solution--they're all correct. Once I created alternate Ozes, it became easy to decide that there was an Oz in which each of the contractions was true. Ozma's hair was both blonde and brunette, depending on which universe you were in. There was also an Oz that corresponded to every incarnation of the books, from the original stage musical to the movies. They all exist. Another advantage of using those paradoxes is that they served as a sort of in-joke to the experienced Oz reader. You pass right by them if you're not in the know, but if you are, there's something special for you. Also, it gives Martin Gardner [the author of THE ANNOTATED ALICE] something extra, in case he wants to annotate the book. All right, he hasn't exactly offered. But see how much fun you would have, Martin, if you did? Thank you, Mr. Einhorn. |

|

FREE Tiger Tales | FREE Tiger Tunes | FREE Tiger Treats

Ordering | Privacy | About Us | Links

All materials are Copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 David Maxine. All rights reserved.

No portion of this website may be used by generative artificial intelligence without written permission.

Website designed by Digital Sourcery

Contact Webmaster | Contact Hungry Tiger Press